Archive for the ‘Contemporary’ Tag

Phylloxera with some reference to Italy by Max Milihan

(i) The Disaster

An aphid typically called phylloxera vastatrix, the devastator, silently made a voyage from the New to the Old World and swept through Europe in the second half of the 19th century. In its trail it left shriveled, fruitless vines on desolate vineyards with confused proprietors in a region of the world that relied heavily upon wine. For the first years the phylloxera remained a misunderstood scourge and for several years afterward an unstoppable enemy. Wine production in France fell 72% in 14 years and put many small, individually owned vineyards out of business (Oxford Companion to Wine). With the combined work of entomologists, biologists, viticulture societies and governments it was overcome in Europe but remains a threat to vineyards across the world today. According again to the Oxford Companion to Wine, ‘about 85 per cent of all the world’s vineyards were estimated in 1990 to be grafted onto rootstocks presumed to be resistant to phylloxera’.

The phylloxera proved difficult to understand because of its odd life cycles and its adaptable nature. The first stage hatches from eggs laid ‘in the previous autumn at the foot of the vine, where it has passed the winter, a very small insect, which travels underground to the end of the most delicate roots, and there nourishes itself by sucking the sap from the vine’ (Jemina 5). This form injects poison into the roots in order to feed on the sap of the roots and begins a colony, producing thousands of offspring. The poison injected opens a permanent canal for the insect to continually feed on the sap of the roots and prevents them from closing and healing. ‘The Phylloxera on the extremities of the roots produces a special and very characteristic kind of swelling which continues to change, or rather to rot, and the vine no longer able to nourish itself, dies’ (Jemina 7). In addition to the form of the phylloxera that feeds on roots, several other forms of the insect have adapted to serve various purposes, such as laying eggs on the underside of the leaves themselves or flying from one plant to another and reproducing. Their procreation is prodigious; botanists and entomologists estimate that millions of the aphids could be produced in one season. In this manner the tiny insects are able to multiply and consume entire vineyards, moving to the next healthy plant after its victim is depleted (Campbell 74).

Early attempts at wine production in the New World by French emigrants had met with disaster. These entrepreneurs brought with them from France their grape vines of the European vitis vinifera variety which had proven to be very effective at producing wine in the Old World (Oxford Companion to Wine). For reasons unknown to them at the time, their experimental vineyards shriveled and died; climate was assumed to be the cause when, in fact, the tiny phylloxera was most likely the reason for the failures (Oxford Companion to Wine). Grape vines native to the New World were able to flourish but produced flavors and aromas that offended the European palette accustomed to the grapes produced by their own vitis vinifera. ‘Attempts to cultivate the European vines were fruitless … but Yankee character is to persevere and native vines were cultivated with great success’ (Campbell 38). Some areas of the continent were able to successfully cultivate the native vines, such as vitis labrusca, vitis aestivalis, vitis rupestris and vitis riparia, and produce wines acceptable to some Americans and a few Europeans while others, most notably California, cultivated vitis vinifera before the phylloxera made their way across the continent.

During the mid-19th century there existed a strong interest in botany, especially in upper-class Victorian England. During the 1850s and 1860s, an American vine called the Isabella proved to be very popular as ornamental decoration in gardens and was shipped en masse into Europe from the United States (Campbell 25). Grape vines had been transferred for years without harm to the environment but, with the invention of a glass box called the Ward Transportation Case in 1835, which kept plants growing on their journey overseas, the parasites feeding on the vines were able to survive the voyage (Campbell 28). Another theory proposes that steam ships made the ocean crossing faster which allowed the aphids to survive the voyage. ‘If [vines] had been infected with aphids, they would have died by the time the long sea voyage was completed. But steamships carried the plants far more quickly and the railway reduced the time of the inland voyage’ (Campbell 108). These vines were rarely used for wine production but they were cultivated in large gardens with nearby vineyards. In this manner, the phylloxera were innocuously introduced to Europe.

(ii) Identification

Due to the life cycle of the phylloxera and their initially slow but exponential spread, the effects of their presence were not observed for several years. The insect was identified as early as 1863 by an entomologist at Oxford named J.O. Westwood after he received samples of the insect from a London suburb (Oxford Companion to Wine), but its effects on native European vines was still unknown. That same year several vineyards in the Rhone region of France were infected but the cause was not apparent until several years later. One of the first documented devastations of vines was written by a French customs inspector, David de Pénanrun, in 1867 who described ‘something wrong with his vines. Leaves were turning brown and falling early. The affliction seemed to spread outwards in a circle’ (Campbell 45). The same year, a veterinarian, Monsieur Delorme, wrote of ‘a small proprietor at Saint-Martin-de-Crau [noticing] leaves on a number of vines turning rapidly from green to red. Within a month ‘most of the vines were already withered and beginning to dry out’’ (Campbell 46).

The phylloxera were not immediately identified as the culprit because ‘when roots had been dug up on dead and dying vines in Floirac scarcely any phylloxera were found’ (Campbell 101). Their life cycle and feeding cycles allow them to move to healthy plants as infected plants are dying. When they were noticed, some speculated that they were a result of the disease, not the cause, and blamed the vine failures on too much rain. Phylloxera reproduce in large quantities during the summer seasons and their winged form allows them to move from plant to plant which resulted in a very rapid spread through Europe. In the years following the first infestations, many surrounding vineyards rotted and the effects sprung up elsewhere in Europe as well, although the main concentration was in France.

In the years following the first reports of vineyard devastation, vineyard owners and agricultural societies reacted quickly to identify the cause and spare their own harvests. The most historically significant push was the creation of the Commission to Combat the New Vine Malady by the Vaucluse Agricultural Society. This society included landowners, horticulturalists, entomologists and and Jules Émile Planchon, the head of the Department of Botanical Sciences at Montpellier University (Campbell 48). They quickly investigated fields with both living and withered vines where Planchon inspected a slowly dying vine;

A happy pickaxe blow unearthed some roots on which I could see with the naked eye some yellowish spots. A magnifying glass revealed them to be clumps of insects… from this moment, a fact of capital importance was established. It was that an almost invisible insect, shying away underground and multiplying there by myriads of individuals, could bring about the exhaustion of even the strongest vine. (Campbell 50)

Despite this discovery, arguments continued to storm over the true cause of the devastation. ‘The greatly respected Henri Marés … declared it was ‘the severe cold that had continued unbroken last winter that is responsible for the deplorable condition of the vines’ (Campbell 51). The following year Planchon, the entomologist Louis Vialla and Jules Lichtenstein were dispatched by the Agricultural Society of France to continue investigation of the aphid; that summer they received correspondence from the State Entomologist of Missouri, Charles Riley. He wrote that the aphids found by Planchon were in fact the same ones that had been studied in the United States, but that they had not had such a disastrous effect on the vines there (Campbell 68). The scientists had found the cause of the devastation and theorized that it came from America, but no cure was yet in sight. The French Commission on the Phylloxera accepted Planchon’s theories and offered a reward of 20,000 francs to whoever could find a cure for the attacks of the aphid (Campbell 80).

(iii) The Fight Back

A French botanist named Léo Laliman who had both American and European vines in his garden reported to the Agricultural Society of France that the American vines had withstood the phylloxera invasion while the European vines had perished (Campbell 71). He proposed a process called ‘grafting’ vineyards ought to fuse the vines of the European vitis vinifera with the roots of the phylloxera-resistant, vitis varieties from America. This process did not combine the genetics of the two plants but rather formed a compound plant; European vines on American roots. Riley, the State Entomologist of Missouri, confirmed that the phylloxera were not fatal to American vines.

We thus see that no vine, whether native or foreign, is exempt from the attacks of the root-louse. On our native vines however when conditions are normal, the disease seems to remain in a mild state and it is only with foreign kinds and with a few of the natives … that it takes on the more acute form. (Campbell 86)

In her account of the phylloxera infestation Christy Campbell remarks that ‘leaf-galling is not fatal to the vine; nor, on American species, are the root predations. Over millennia of evolution wild vines developed ways to keep the attacker at bay … European vine-roots had and have no such defences’ (Campbell 77).

American resistance had been established but few took note of Laliman’s grafting proposal; grafting was not immediately used as many believed that it would reduce the quality of the grapes produced. Many potential remedies were tested to no avail; Riley remarked that ‘all insecticides are useless’ (Campbell 124). It was not until 1876 that Jean-Henri Fabre reported on his vineyards of ‘grafted Aramons on American varieties’; he said that ‘[the grafted vines] produced no alteration in the quality of taste of the wine nor had any influence on the [resistant] constitution of the roots’ (Campbell 154).That same year Planchon advocated the same thing. ‘While the power of the rootstock directly influences the development of the transplant, the rootstock does not transmit the particular taste which it would have in its own grapes’ (Campbell 160).

Despite rare successes from experimental vineyards grafted onto American rootstock, many still believed that insecticides would be the cure. As such, the French government briefly implemented a ban on the importation of American vines that would prove only to delay the eventual remedy. Lichtenstein, one of the members of the phylloxera investigation, published statements urging the expanded use of grafts. He wrote that ‘the wines of France will live again, reborn on the resistant rootstocks of America’ (Campbell 195).

Campbell describes how ‘slowly, slowly, reconstitution [grafting] took place. When the Beaujolais was officially declared phylloxerated in 1880, the import of alien vines became legal’. According to the French Ministry of Agriculture, about a third of France’s vineyards had been transplanted onto grafted or hybridized vines (Campbell 235).

After twenty years of anguish and effort the vineyards of [southern France] had been put together again. The costs had been great, debts were pressing, but by the mid-1890s the reconstituted vineyards were producing a flood of wine for which there seemed to be no end of thirst. (Campbell 247)

Even into the 1920s there were still un-grafted vineyards surviving on expensive chemical defenses. Today still there are vineyards in Australia, South America, the Middle East and scattered islands that survive on ungrafted vines because of soil conditions or strict controls preventing the movement of phylloxera. But, as noted before, it is estimated that 85% of the world’s vineyards are planted on grafted rootstocks (Oxford Companion to Wine).

(iv) The Battle in Italy

Although the effects of the phylloxera crisis were felt the most in France, it affected much of Western Europe. Professor Battista Grassi estimated that only about 10% of the country’s vines were infected by 1912; ‘the reason for its slow spread was the comparatively isolated nature of Italian vineyards and the habit of growing many vines through trees’ (Ordish 172). The first report of phylloxera in Italy was near Lake Como, but the regions struck hardest were Sicily and Calabria. In a New York Times article published November 8th, 1895 the Italian Consul estimated that lost wages in Sicily in the early 1890s totaled over thirty million dollars (‘Phylloxera Ravages Italy’). Many vineyard owners actually saw the infestation in France as an economic opportunity to export their own wines. In fact, in 1909 five million hectoliters of Italian wine exports to France made up about 10% of the wine consumed by the French (Campbell 249).

As the infestation struck Italy later on and much more slowly, its eradication was much more easily addressed in Italy than in France. Italy, along with many other European countries, enacted a temporary ban on plants that might carry the phylloxera into their vineyards. Vineyards found infected early on were burned at the expense of the state in order to slow the spread (Ordish 173). Although the burning of infected vineyards benefited the Italian wine industry as a whole, there were negative reactions from the owners and workers; in August of 1893 the New York Times reported that ‘the Minister of Agriculture … recently ordered the destruction of vineyards covering a large area in the Province of Novara. The peasants, losing employment through these steps, began to riot. Many were injured in conflicts with the police, and a large number were arrested’ (‘Italian Peasants Rioting’). Once grafting was accepted as a solution the ban on imported vines was lifted in order to supply Italian vineyards with resistant rootstocks subsidized by the government. In fact, another New York Times article published February 2, 1892 indicates that ‘the Italian Minister of Agriculture has for a number of years distributed large quantities of American grape vines among the farmers’ and that ‘from the island of Sicily alone the Minister has received demands for twenty six million rootstocks’ (‘American Vines in Italy’). The government supplied American cuttings and seeds, along with subsidies to farmers planting New World vines (Ordish 173). The Turin Phylloxera Council published their notes from an 1880 meeting, remarking that ‘we, knowing the danger, shall be able in great part to avoid it … Italy having to fight against Phylloxera finds herself in a more favourable position, being abundantly supplied with American vines, which are known to resist the disease’ (Jemina 3). As a result of the later introduction, slower spread and governmental subsidies, Italy’s vineyards were damaged far less than those of France.

‘AMERICAN VINES IN ITALY’ Editorial. New York Times 2 Feb. 1892. The New York Times. Web. 06 Dec. 2010. <http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=FB0D15FC355D15738DDDAB0894DA405B8285F0D3>.

Campbell, Christy. Phylloxera: How Wine Was Saved for the World. London: HarperCollins, 2004. Print.

‘Italian Peasants Rioting’ Editorial. New York Times 4 Aug. 1893. The New York Times. Web. 06 Dec. 2010. <http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=F50D13F93F5A1A738DDDAD0894D0405B8385F0D3>.

Italy. The Turin Phylloxera Council. The Turin Phylloxera Council: Ideas as to the Phylloxera and Rules for Watching the Vineyards. By Jemina. Turin, 1887. John Rylands University Library. Web. 7 Dec. 2010. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/60231304>.

Ordish, George. The Great Wine Blight. London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1987. Print.

‘PHYLLOXERA RAVAGES ITALY’ Editorial. New York Times 08 Nov. 1895. The New York Times. Web. 06 Dec. 2010. <http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=FB0A15FE355911738DDDA10894D9415B8585F0D3>.

Robinson, Jancis. The Oxford Companion to Wine. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999.

The following article appeared in the Irish Times 24 Dec 2010: the original can be found here in this excellent piece by Ken Doherty. SY

It is sometimes said that a good year for wine is a bad year for truffles. Something to do with a sufficient amount of rain satisfying the grape but sadly not enough to yield a crop of truffles. As we strolled around the pretty cobbled streets of Alba in northwest Italy – the go-to town for the truffle-nut – it looked like a bumper year for the musty fungal.

The town was overcome with truffle triumphalism. Every other shop window was festooned with the real thing or jokey simulacrums to excite the tourists. Having only tasted black truffles, and this being the truffle season, it was the pungency of its white relation that we were after. It started with a plan. The family, two adults and a baby, would, on a tour of the fertile north of Italy, make their way to the food and wine rich trinity of Gavi, Asti and Alba. Setting off from our base at a wonderful agriturismo (countryside BB), we would gobble as much of the region’s culinary specialities as we could.

As the bus rumbled its way up the narrow roads towards the village of Gavi in Piemonte, we sensed a treat in store. Gavi doesn’t just rely on its spectacular setting to woo you in. Its sumptuous vistas are a close second to its main draw. People make the pilgrimage to this tiny hamlet to experience its famous sweet and acidic white wines. We came for both.

Most of its wineries are just outside the town and, since we were car-free and baby-tied, we explored its medieval centre on foot. Its compact and charmingly dilapidated streets and buildings were quiet by late afternoon. On its main drag we stumbled into Antico Caffe Del Moro, pasticceria-bar-canteen-ice cream parlour and breast feeding refuge all rolled into one. We quickly fell prey to the proprietor’s big-hearted welcome and were given an introductory lesson to the intricacies of viniculture in Gavi.

After a quick feed from her mammy, all this nattering had a soporific effect on the baby. We were afforded a few tastings of what the Gavi vintage (from the Cortese grape) and its regional wines had to offer. This braced us for one of the many decent walks around the town.

Asti was different. It bristles with a more rugged atmosphere, especially during the twice weekly outdoor market days. Traders set up stall every Wednesday and Saturday in Campo del Palio but disappear by late afternoon. When we arrived at noon it was in full flow.

Amid all the cheaply-made threads and kitchen paraphernalia there is a wonderful food market that spoke of the season we were in. Stalls heaving with knobbly mushrooms, voluptuous squash and sultry plums made our bellies rumble.

The banter between stall holders and customers was imbued with typical Italian feeling – wildly gestating hands performing in the narrowest personal space possible. And for those who like to overturn historical myths and inaccuracies, the square is spiked with significance. Every September it hosts a bareback horse race similar to the famous Palio in Siena, Tuscany. But wait. In Asti, they claim their race is at least 300 years older!

Alba has the confident air of a regional capital. Situated in the rolling hills of the Langhe, it’s hemmed in by the vineyards that produce the famous Barolo, Barbera and Barbaresco wines. From the bus stop it’s only a short walk to the old town. We noticed that if your appetite wasn’t sated by wine and truffles, you could always undergo some retail therapy in its many expensive designer boutiques.

It was getting late and we were the ones who might need clinical gastronomic therapy if we didn’t see some truffle action soon. We skipped into Vincafe on Via Vittorio Emanuele and were not disappointed. The place was buzzing.

We started with some silky lardo (pure cured pork fat) that sweetly lined our stomachs for what was to come. I swear I could hear the drums roll as our truffle dishes made their way from the kitchen. Both dishes, baked eggs ( cocotte con tartufo bianco ) and pasta ( tagliarini con tartufo ) were decorated with wisps of white truffle. The price did make the eyes water but what the hell, I now understand why a lot of chefs choose it as a death row last meal.

Gavi, Asti and Alba are repositories of all that is good about Italy. Fantastic food, unforgettable scenery and a genuinely warm welcome. So make your way to this part of the peninsula, hardly undiscovered, but a region steeped in such significant culinary lore it can only be a gift that keeps on giving.

The following is the beginning of a fascinating article by Laurel Curran on Italian food safety that can be found here.

‘When you think of Italian food, the first dishes that come to mind are probably pizza and pasta. I am here to tell you that’s not just your imagination. Those carb-saturated items make up the majority of a typical Italian’s diet (plus gelato, of course). It took about five weeks for my body to adjust from my Pacific Northwest diet of seafood, granola and vegetables to one consisting almost entirely of these items. After four months living in Rome, I have decided that Italians love carbohydrates even more than Americans do.This is interesting when one considers the fact that there are virtually zero obese Italians. Not only do they know how to make carbs unbelievably tasty, they know how to eat them right. Maybe it’s because they don’t serve butter with their bread, maybe it’s because their pasta portions are the size of something off an American kids’ menu and maybe it’s because they walk everywhere. Whatever the reason, Italians have food figured out.When it comes to food safety they also fare quite well. Italy suffers far fewer foodborne illness outbreaks per capita than the United States. There have been only a handful in the past decade. Most have been at hotel and resort restaurants, and none have affected more than 60 people. There are no food safety law firms in Italy for a reason. When I asked my neighborhood shopkeeper about this he suggested that the food he sells is safe because the EU became hyper-vigilant after the Mad Cow disease outbreak in 2001. He’s right; the EU has some very stringent laws protecting European consumers [continues]

…‘

In an article which barely concealed its gleeful tone, a recent article in the Italian newspaper La Repubblica (13 Jan 2011, p.18) noted that marmalade, the traditional British breakfast  spread, was losing ground fast to both Italian Nutella and, even worse, to American brands of peanut butter. In calendar year 2010, 2.5 million jars fewer of the sugary-but-bitter spread made with Seville oranges were sold in the United Kingdom than in 2009. The article quoted Xanthe Clayr of the Daily Telegraph, who called the drop in marmalade sales a “tragedy,” and who said that something must be done as marmalade “is one of the best culinary traditions of our country.” Over half of the consumers of marmalade are over 65 years old, and in addition to the an image problem, a rise in the price of honey has hurt marmalade sales. What’s worse, coffee (pushed by American chains and Italian brands in the supermarkets) has surpassed tea as the hot beverage of choice on British mornings, spaghetti often outsells sausage and beans, and wine is rapidly catching up to beer.

spread, was losing ground fast to both Italian Nutella and, even worse, to American brands of peanut butter. In calendar year 2010, 2.5 million jars fewer of the sugary-but-bitter spread made with Seville oranges were sold in the United Kingdom than in 2009. The article quoted Xanthe Clayr of the Daily Telegraph, who called the drop in marmalade sales a “tragedy,” and who said that something must be done as marmalade “is one of the best culinary traditions of our country.” Over half of the consumers of marmalade are over 65 years old, and in addition to the an image problem, a rise in the price of honey has hurt marmalade sales. What’s worse, coffee (pushed by American chains and Italian brands in the supermarkets) has surpassed tea as the hot beverage of choice on British mornings, spaghetti often outsells sausage and beans, and wine is rapidly catching up to beer.

Though the Repubblica doesn’t mention this, Britain shouldn’t feel like it stands alone, even though its “traditional foods” are threatened. Culinary philologists all over the world will likely form brigades to help Britannia purge its food of foreign influences like…Seville oranges. And Indian curry. And Chinese tea. ZN

Salone del Gusto by Gabriella Paiella

On Friday, October 22nd 2010, four friends and I made our way up north for Salone del Gusto and Terra Madre. The trip was initially up-in-the air as we had only managed to secure a spot at a hostel on the outskirts of Torino a few days before – the city had been booked up for the event since July. Bright and early the next morning, we caffeinated and began the brisk forty-minute walk to the old Fiat factory where the event has been held for several years. The festival was a clear economic boost to the city of Torino and signs everywhere advertised the Salone del Gusto and pointed tourists in the correct direction.

The first people we encountered at the fringes of the factory grounds were animal rights protesters brandishing gruesome signs of slaughtered animals with statistics of how many animals had been murdered for Salone del Gusto. We avoided them as best as we could and made our way to the line, which was organized and moved forward quickly despite the extraordinary numbers of people. Because we were all under 23, we could get access to the festival for the student rate of 12 euro each.

The theme of the Salone this year was ‘Food + Places: a new geography for Planet Earth’. Upon entering, we found ourselves in a spacious, and well-lit main room with the atmosphere of an IKEA store. Indeed, every booth on this floor was advertising possible eco-friendly solutions to food packaging. Aside from a few curious visitors, most people avoided this first room in favor of the food fair itself – which was packed to the brim.

Salone was split up into several sections. First and foremost was ‘Italy’, – divided up like a grid according to region. We tried almost everything, including lenticchie from Umbria, peperonata from Piedmont, and cannoli from Sicily. It also seemed as if every other stand was sampling some sort of olive oil and bread. My traveling companions and I were surprised (and pleased), by the overwhelming amount of artisanal beer from Italy. All of the producers were extremely friendly and took the time to answer any questions we had for them about their products.

The international section was comprised of representative producers from everywhere from America to Azerbijan. In the middle of all of the food stalls were tables manned by indigenous representatives from Latin America and Africa. Many of them had spoken at Terra Madre and were selling handicrafts and distributing fliers about the current state of agriculture and small farms in their home countries.

There were also more specific novelty areas – such as the ‘Cocktail Bar,’ ‘Enoteca,’ and ‘Street Food’ area, though those were both significantly less crowded than the other sections. This was most likely due to the fact that visitors had to pay extra to access them.

The demographics of the crowd were incredibly mixed. Every once in a while, a Native American farmer in indigenous dress would pop through the fair grounds with their Terra Madre delegate badge on. At the same time, there were several hundred well-dressed Italians teetering around in high heels and purchasing bags of wine and olive oil – making me wonder if they actually ever thought twice about the ideology of Slow Food. The stark difference between the two groups was interesting.

I was also surprised to see Autogrill and Coop stands scattered amongst the other stands. I knew that the Coop supermarkets had initially started as small cooperative movements on the left, but they have certainly strayed far from that model. Autogrill, meanwhile, seems to exemplify the very nature of fast food.

Even when we left Salone del Gusto and headed back to our hostel, we still felt as if we were in that general atmosphere. Everyone staying with us was in the city for the same reasons we were. For example, I met a girl from North Carolina studying abroad in Dijon and compiling an independent research project on organic food regulations. Another one of my roommates graduated from the college that I’m attending right now ten years ago; she was in Torino visiting her sister who acts as a liaison between farmers and farmer’s market organizers. One girl had graduated college in the States and moved to Rwanda to help AIDS victims set up small, microfinance farming operations. Additionally, we met two chefs: one from Lecce who had previously traveled around Europe acting out in “Chef’s Theater” plays. The other was a Brazilian who was hopping around Europe and getting by working at restaurants all over the continent.

As we all stayed up that night talking, I realized that there was a strong and diverse community of people dedicated to bettering the global food system.

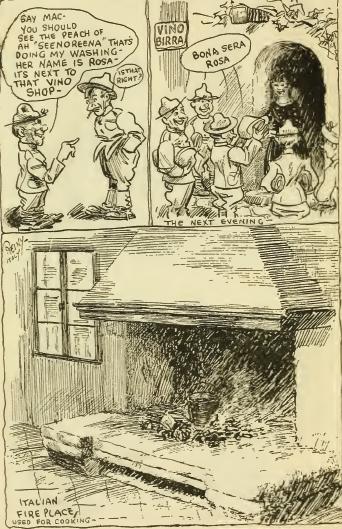

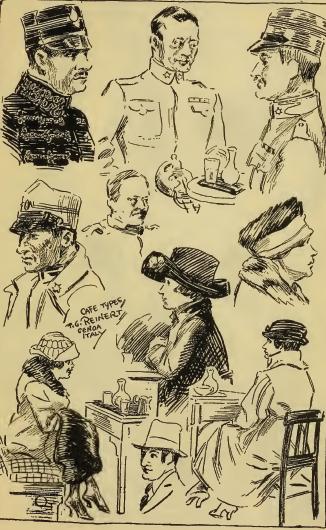

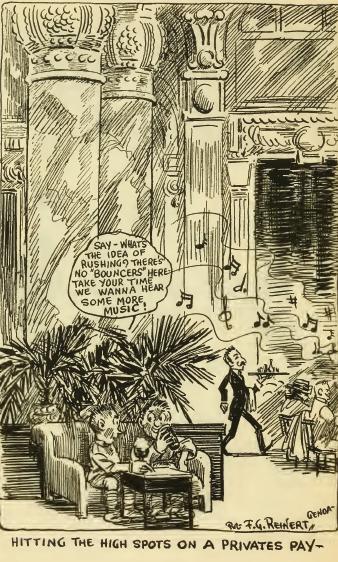

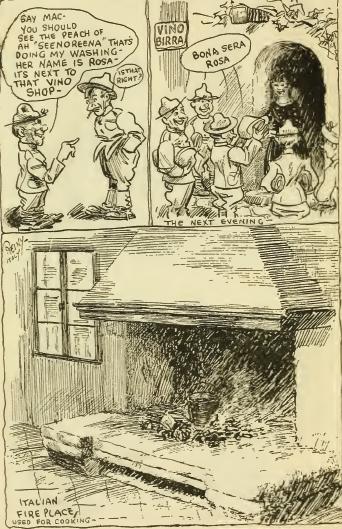

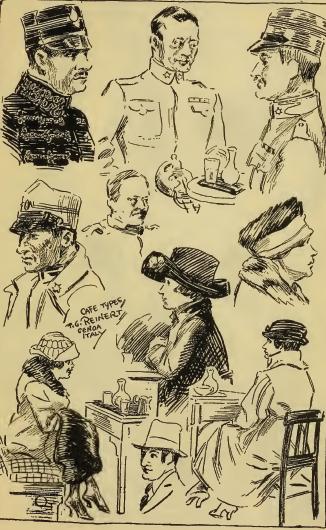

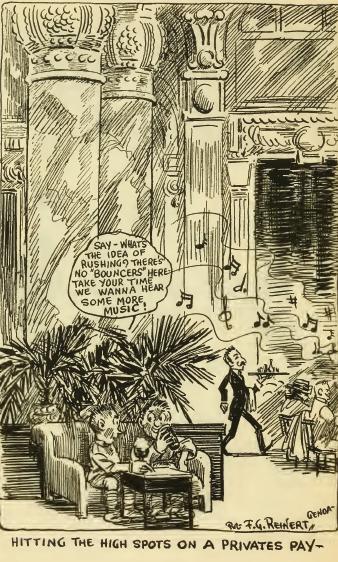

The following pictures were drawn by Reinert and appeared in his hilarious With the 332 Reg. in ’18 Italy ’19. We have extracted some of the images concerning food, showing Italy as the land of fun and scarcity in the late First World War and its aftermath. SY

Italian Jewish Cooking by Tom Albert

i) Introduction and Artusi

Pellegrino Artusi published in 1891 the best known of all Italian cookbooks: La Scienza in Cucina. In this cookbook, Artusi mentions the Jews and their cooking in Italy.

‘Forty years ago, one hardly saw eggplants or fennel in the markets of Florence; they were considered to be vile because they were foods eaten by Jews. As in other matters of greater moment, here again the Jews show how they have always had a better nose than the Christians’ (Artusi 1890, §399).

Artusi’s quote sums up the Italian perception of the Jewish presence in Italy. In it we see the anti-Semitism present in Italy – the nose joke – but also the melding of Italian and Jewish foodways. Artusi’s quote also indirectly demonstrates how little information there is about Italian Jewish cooking, since this paragraph is the only important nineteenth-century source we have on this topic.

ii) Italian Jewish Communities

Italian Jews fell into three categories: Italkim, Sephardim, and Ashkenazim (Goldstein, 1998). The Italkim arrived in Rome in 2 B.C. The Sephardim immigrated from Spain and Portugal in 1492 right after the Spanish government drove them from the country. Lastly, the Ashkenazim were from central Europe and settled in the north of Italy.

These three groups each brought with them specific foods. For example, the Sephardic Jews brought New World food to Italy, including peppers, tomatoes, potatoes, corn and pumpkin (Goldstein, 1998). Ashkenazim tended to use more spices, while the Italkim utilized the regional foods of Italy (Serbe-Viola).

Once the Jews arrived in Italy, most settled throughout Italy: Rome, Turin, Piedmont, and Sicily (Stille, 1991) (Goldstein, 1998). Anti-Semitism was present in Italy and thus the Jews were ghettoized. They were isolated and shamed as we see in one notable Florentine Renaissance source: ‘Every Jew, male or female above the age of twelve, whether or not named in the Florence agreement, and whether or not a resident of the city of Florence shall be required to wear a sign of O in the city of Florence’ (Bucker). There was a penalty of 25 lires for those that forgot to wear it (Bucker).

Their isolation and public dislike did not bode well for their economic status, and they were, for the most part, poor. Their diet consisted, then, of the classic Mediterranean staples: olive oil, wine, little meat, and ‘poor’ vegetables (such as onions and garlic). In addition, in the ghetto, there was a mixture and mixing of Jewish traditions. This blend of customs obviously affected cuisine. The Italkim could share with the Sephardim and Ashkenazim their New World food, while Ashkenazim introduced their Jewish counterparts to spices.

Their diet was also influenced by the region that they lived in. Since Sicily was a center for Mediterranean trade, Jewish cooking was influenced by Arabic, Norman, Arogonese and later Spanish cuisine (Goldstein, 1998). The Jews incorporated Arabic cuisine especially, with the use of sweet and sour dishes, as well as pine nuts and raisins. However, the Spanish Inquisition effectively drove many Jews out of the southern island, which was under Spanish control (Goldstein, 1998). They moved ‘to Ancona and Pesaro, most to Rome, where their Arab-inspired dishes entered Roman culture’ (Goldstein, 1998). In addition, since the Jews migrated to separate parts of Italy, and, as Italy was not unified until 1861, Italian Jewish cuisine changed with the regions. Since the Jews were forced to move constantly due to persecution, they had to adapt to the local ingredients and shape them around their Kosher laws.

Nevertheless, Italy’s unification represented a change for the Jewish people of Italy. Once they were allowed to leave the ghetto, they took on the identity of Italian first, Jewish second (Goldstein, 1998). This was the time of assimilation. The Jews in Italy held high-power jobs, such as generals, cabinet ministers, and prime ministers (Stille, 1991). ‘The distinction between Jews and non-Jews didn’t exist…there were some religious Jews, but they tended to be poorer, closer to the roots’ (Stille, 1991).

iii) Jewish Cooking

Assimilation meant the loss of many Jewish traditions and in this changing world, cooking was one precious link with the past. As Lucia Levi had it in the introduction to Poesie Nascosta (1931) the first Jewish Italian cookbook:

‘Vi sono forme delle tradizioni culinarie proprie ad ogni paese, ad ogni regione, qualche volta ad ogni famiglia. Spesso tali tradizioni sono le solo sopravvissute in mezzo al più desolante abbandono di ogni abitudine ebraica. Tenendole nel giusto onore Israele non rimpicciolisce la religione ma realizza quella che è l’essenza stessa dell’ Ebraismo, spiritualizza cioè i più umili materiali atti della vita, identificandoli con l’atto più elevato cioè la preghiera, la comunione con Dio.’

[‘There are forms of cooking tradition in every country, every region and sometimes in every family. Often these traditions are the last survivors in the midst of the complete abandonment of every Jewish custom. Holding cooking in proper honour Israel does not diminish religion but underlines what is the essence of Judaism, to spiritualise the most humble material acts in life, identifying them with the highest act – prayer and the communion with God.’]

Assimilation also meant that many Italian Jewish families no longer kept a kosher home. Yet, they still celebrated holidays, but with more emphasis on food than the historical importance of what the holiday represented (Goldstein, 1998). For example, during a Passover Seder, they had ‘buttered sandwiches of anchovy paste, smoked salmon, caviar, pate de foie gras, ham; with little volau-vents filled with minced chicken in béchamel…the ham and chicken in béchamel are clear violations of the kosher laws’ (Goldstein, 1998). Jewish identity was ‘more a matter of family tradition and honor than spiritual commitment…they were proud of being Jewish…[and] proud of being Italian’ (Stille, 1991). With this assimilation, even though it meant more equality between Jewish Italians and Italians, it also meant that Jewish laws, which are a crucial part of the religion, were being forgotten.

So, what exactly is Jewish Italian cooking? This is a hard question to answer because there are not many sources out there that discuss this specific topic. The first published Italian cookbook, Poesia Nascosta, did not appear until 1931, and by this time, assimilation was at its climax (Siporin, 1994). Jewish cooking for the Italians represented ‘unforgettable memories of ceremonies, of family reunions that have left a sense of nostalgic sweetness and delicious dishes in the hearts of everyone’ (quoted from Siporin, 1994). In Italy, nostalgia began to define Jewish cooking. ‘More recent Italian Jewish cookbooks further diminish the role of Kashrut and correspondingly expand the role of nostalgia in defining cucina ebraica’ (Siporin, 1994). In another Italian Jewish cookbook, the author mentions that he hopes that Jewish dishes ‘become a tasty pretext for discovering (or rediscovering) the pleasant aroma of our holidays, which seemed lost forever’ (quoted from Siporin, 1994). In addition, Italian Judaism in Italy has ‘been sentimentalized and recast in terms of family tradition in the kitchen’ which helps explain the nostalgia that comes from the meals (Siporin, 1994).

This nostalgia is evident today. Italy’s leading Jewish website – www. Torah.it – includes two Jewish Italian cookbooks in its corpus of Jewish Italian works. It is there too in the name and tone of many more modern Italian Jewish works of cookery including La Cucina della Memoria [The cooking of memory] Ricete giudaico-monferrine raccolte dai ricettari di famiglia, a cura della comunita ebraica di Casaie Monferrato, Fondazione arte e storia della cultura ebraica a Casale Monferrato e nel Piemonte orientale, (2001).

Yet, besides nostalgia, Jewish Italian dishes also took the pattern of the Italian menu, with a primo piatto, secondo piatto, contorni, and dessert (Siporin, 1994). This regular form ‘is so common in Italy that it is almost invisible’ (Siporin, 1994). It also made a statement ‘of class association through one’s ability to adhere to the structural formula’ (Siporin, 1994). Jewish Italians felt that in order to show their participation in the culture, they had to show that they understood and contributed in culinary refinement. The Italian Jewish cookbooks ‘apply the Italian meal formula to each Jewish holiday, so that menu tradizionali have been constructed for every seasonal celebration. In other words, there are set, four to give course meals for Purim, Passover, Shavuot, and other holidays’ (Siporin, 1994). Even the cookbook themselves are organized according to the Italian menu, with sections for meats, soup, and vegetables in the ‘sequenced order of the meal’ (Siporin, 1994). This demonstrates how much the Jews assimilated the Italian culture into their own. ‘The form of the meal-even on the most Jewish of days-is Italian. And the contents and occasions of these elegant Italian constructions are anciently and locally Jewish’ (Siporin, 1994). Italian Jews are making it very clear that they contain both identities, allowing both to shine simultaneously.

Yet, even with the two identities mixing, there is still the inevitability of the diminishing presence of the Jewish religion. Modern cookbooks do evoke a sense of nostalgia and express pride in being Jewish. ‘They also serve to secure a place for ‘Jewish cuisine’ in the pantheon of ‘regional’ Italian cuisine’ (Siporin, 1994). The importance of the religion has faded, but the cuisine reflects ‘an identity that… is still valued’ (Siporin, 1994).

Artusi, Pellegrino, Murtha Baca, and Stephen Sartarelli. Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well. Toronto: University of Toronto, 2003. Print.

Brucker, Gene The Society of Renaissance Florence, 241-243.

Goldstein, Joyce Esersky. Cucina Ebraica: Flavors of the Italian Jewish Kitchen (San Francisco, 1998)

Serbe-Viola, Diana. ‘Jewish Cooking – Foods of the Diaspora’ In Mamas Kitchen. Web. 06 Dec. 2010. <http://www.inmamaskitchen.com/FOOD_IS_ART_II/food_history_and_facts/Jewish_Cooking.html>

Siporin, Steve ‘From Kashrut to Cucina Ebraica: The Recasting of Italian Jewish Foodways’, The Journal of American Folklore, 107 (Spring, 1994), 268-281

Stille, Alexander. Benevolence and Betrayal: Five Italian Jewish Families under Fascism. (New York 1993)

Papin's "digester"

In a recent article in the Italian newspaper La Repubblica (2 January 2011, p.41), food historian Massimo Montanari celebrated the invention of what was originally called the “machine for softening bones.” This happy machine, created by Frenchman Denis Papin, was presented to the world in a book published in London in 1681. The bone digester could also be used for (explained Papin in his book) reducing the time required for cooking foods, thus saving on valuable fuel. Papin’s invention, then, was the precursor of the modern pressure cooker, though Montanari points out that one of the main problems was the regulation of the pressure inside to prevent explosions. Later versions included a pressure release valve. Papin’s digester came to Italy soon after its creation: Montanari tells us that it was popularized by the Venetian Ambrogio Sarotti, and used to make medicinal decoctions and broths by a certain Sangiorgiofrom Milan (prefiguring German chemist Justus von Liebig’s extracts). This machine not only provided the basis for the pressure cooker: the autoclave, the steam engine, and even the Italian home coffee maker (called a “Moka”) are children of Papin’s genius.

Several students from the Umbra Institute food programme voted this Christmas on Perugia’s best eating spot, after a semester of delectation and growing expertise in food matters. Here are the results. Congratulations to the Osteria del Tempo Perso and Al Mangiar Bene. SY

Osteria del Tempo Perso: 12

Al Mangiar Bene: 10

Mediterranea: 6

Dal mi cocco: 5

Pizza e Musica: 4

La Taverna: 2

Pizzeria Etrusca: 2

Trattoria del Borgo: 2

Il Baldo: 1

La Cambusa: 1

Il Tempio: 1

La Victoria: 1

Luna Bar: 1

There is a well known ‘food myth’ about Montefiascone wine and a German bishop. The following account is taken from Edward R. Emerson, Story of the Vine (Knickerbocker Press 1902). It would be interesting to see how much older the tale is.

As the story goes… a German bishop named Defoucris, who travelled a great deal, and had acquired in his many journeys a discriminating fondness for wine. His valet bibulous bishop. was also an excellent judge, and the bishop, in order to ascertain the quality of the wine at the places where he was to stop, would send the valet on ahead that he might test it and write under the bush the word ‘est’ if it was good, and ‘est est’ if it was fine. On the other hand, if it was poor the valet was to leave a blank under the bush; at such places the bishop refused to drink.

The bush is a bunch of evergreen hung over the doorway to tell travellers ‘here wine is sold’. It has been used from time immemorial, and it is from its use that the saying ‘Good wine needs no bush’ has arisen, several of our noted authorities notwithstanding. At last the valet, arriving at Monte Fiascone, found there a place where he could write ‘est est’. In due time the bishop arrived, and was so pleased with the wine that he immediately proceeded to get drunk on it, and remained in that condition until he died.

The legend was either given in an incomplete form or it has since developed. This is extracted from the Italian Wikipedia inDecember 2010.

Il nome di questo vino deriva da una leggenda. Nell’anno 1111 Enrico V di Germania stava raggiungendo Roma con il suo esercito per ricevere dal papa Pasquale II la corona di Imperatore del Sacro Romano Impero. Al suo seguito si trovava anche un vescovo, Johannes Defuk, intenditore di vini. Per soddisfare questa sua passione alla scoperta di nuovi sapori, il vescovo mandava il suo coppiere Martino in avanscoperta, con l’incarico di precederlo lungo la via per Roma, per assaggiare e scegliere i vini migliori. I due avevano concordato un segnale in codice: qualora Martino avesse trovato del buon vino, avrebbe dovuto scrivere est, ovvero ‘c’è’ vicino alla porta della locanda, e, se il vino era molto buono, doveva scrivere est est. Il servo, una volta giunto a Montefiascone e assaggiato il vino locale, non poté in altro modo comunicare la qualità eccezionale di quel vino, decise di ripetere per tre volte il segnale convenuto e di rafforzare il messaggio con ben sei punti esclamativi: Est! Est!! Est!!! Il vescovo, arrivato in paese, condivise il giudizio del suo coppiere e prolungò la sua permanenza a Montefiascone per tre giorni. Addirittura, al termine della missione imperiale vi tornò, fermandosi fino al giorno della sua morte (avvenuta, pare, per un eccesso di bevute). Venne sepolto nella chiesa di San Flaviano, dove ancora si può leggere, sulla lapide in peperino grigio, l’iscrizione: ‘Per il troppo EST! qui giace morto il mio signore Johannes Defuk’. In riconoscenza dell’ospitalità il vescovo lasciò alla cittadinanza di Montefiascone un’eredità di 24.000 scudi, a condizione che ad ogni anniversario della sua morte una botticella di vino venisse versata sul sepolcro, tradizione che venne ripetuta per diversi secoli. Al vescovo è ancora dedicato un corteo storico con personaggi in costume d’epoca, che fanno rivivere questa leggenda.

SY

Phylloxera with some reference to Italy by Max Milihan

(i) The Disaster

An aphid typically called phylloxera vastatrix, the devastator, silently made a voyage from the New to the Old World and swept through Europe in the second half of the 19th century. In its trail it left shriveled, fruitless vines on desolate vineyards with confused proprietors in a region of the world that relied heavily upon wine. For the first years the phylloxera remained a misunderstood scourge and for several years afterward an unstoppable enemy. Wine production in France fell 72% in 14 years and put many small, individually owned vineyards out of business (Oxford Companion to Wine). With the combined work of entomologists, biologists, viticulture societies and governments it was overcome in Europe but remains a threat to vineyards across the world today. According again to the Oxford Companion to Wine, ‘about 85 per cent of all the world’s vineyards were estimated in 1990 to be grafted onto rootstocks presumed to be resistant to phylloxera’.

The phylloxera proved difficult to understand because of its odd life cycles and its adaptable nature. The first stage hatches from eggs laid ‘in the previous autumn at the foot of the vine, where it has passed the winter, a very small insect, which travels underground to the end of the most delicate roots, and there nourishes itself by sucking the sap from the vine’ (Jemina 5). This form injects poison into the roots in order to feed on the sap of the roots and begins a colony, producing thousands of offspring. The poison injected opens a permanent canal for the insect to continually feed on the sap of the roots and prevents them from closing and healing. ‘The Phylloxera on the extremities of the roots produces a special and very characteristic kind of swelling which continues to change, or rather to rot, and the vine no longer able to nourish itself, dies’ (Jemina 7). In addition to the form of the phylloxera that feeds on roots, several other forms of the insect have adapted to serve various purposes, such as laying eggs on the underside of the leaves themselves or flying from one plant to another and reproducing. Their procreation is prodigious; botanists and entomologists estimate that millions of the aphids could be produced in one season. In this manner the tiny insects are able to multiply and consume entire vineyards, moving to the next healthy plant after its victim is depleted (Campbell 74).

Early attempts at wine production in the New World by French emigrants had met with disaster. These entrepreneurs brought with them from France their grape vines of the European vitis vinifera variety which had proven to be very effective at producing wine in the Old World (Oxford Companion to Wine). For reasons unknown to them at the time, their experimental vineyards shriveled and died; climate was assumed to be the cause when, in fact, the tiny phylloxera was most likely the reason for the failures (Oxford Companion to Wine). Grape vines native to the New World were able to flourish but produced flavors and aromas that offended the European palette accustomed to the grapes produced by their own vitis vinifera. ‘Attempts to cultivate the European vines were fruitless … but Yankee character is to persevere and native vines were cultivated with great success’ (Campbell 38). Some areas of the continent were able to successfully cultivate the native vines, such as vitis labrusca, vitis aestivalis, vitis rupestris and vitis riparia, and produce wines acceptable to some Americans and a few Europeans while others, most notably California, cultivated vitis vinifera before the phylloxera made their way across the continent.

During the mid-19th century there existed a strong interest in botany, especially in upper-class Victorian England. During the 1850s and 1860s, an American vine called the Isabella proved to be very popular as ornamental decoration in gardens and was shipped en masse into Europe from the United States (Campbell 25). Grape vines had been transferred for years without harm to the environment but, with the invention of a glass box called the Ward Transportation Case in 1835, which kept plants growing on their journey overseas, the parasites feeding on the vines were able to survive the voyage (Campbell 28). Another theory proposes that steam ships made the ocean crossing faster which allowed the aphids to survive the voyage. ‘If [vines] had been infected with aphids, they would have died by the time the long sea voyage was completed. But steamships carried the plants far more quickly and the railway reduced the time of the inland voyage’ (Campbell 108). These vines were rarely used for wine production but they were cultivated in large gardens with nearby vineyards. In this manner, the phylloxera were innocuously introduced to Europe.

(ii) Identification

Due to the life cycle of the phylloxera and their initially slow but exponential spread, the effects of their presence were not observed for several years. The insect was identified as early as 1863 by an entomologist at Oxford named J.O. Westwood after he received samples of the insect from a London suburb (Oxford Companion to Wine), but its effects on native European vines was still unknown. That same year several vineyards in the Rhone region of France were infected but the cause was not apparent until several years later. One of the first documented devastations of vines was written by a French customs inspector, David de Pénanrun, in 1867 who described ‘something wrong with his vines. Leaves were turning brown and falling early. The affliction seemed to spread outwards in a circle’ (Campbell 45). The same year, a veterinarian, Monsieur Delorme, wrote of ‘a small proprietor at Saint-Martin-de-Crau [noticing] leaves on a number of vines turning rapidly from green to red. Within a month ‘most of the vines were already withered and beginning to dry out’’ (Campbell 46).

The phylloxera were not immediately identified as the culprit because ‘when roots had been dug up on dead and dying vines in Floirac scarcely any phylloxera were found’ (Campbell 101). Their life cycle and feeding cycles allow them to move to healthy plants as infected plants are dying. When they were noticed, some speculated that they were a result of the disease, not the cause, and blamed the vine failures on too much rain. Phylloxera reproduce in large quantities during the summer seasons and their winged form allows them to move from plant to plant which resulted in a very rapid spread through Europe. In the years following the first infestations, many surrounding vineyards rotted and the effects sprung up elsewhere in Europe as well, although the main concentration was in France.

In the years following the first reports of vineyard devastation, vineyard owners and agricultural societies reacted quickly to identify the cause and spare their own harvests. The most historically significant push was the creation of the Commission to Combat the New Vine Malady by the Vaucluse Agricultural Society. This society included landowners, horticulturalists, entomologists and and Jules Émile Planchon, the head of the Department of Botanical Sciences at Montpellier University (Campbell 48). They quickly investigated fields with both living and withered vines where Planchon inspected a slowly dying vine;

A happy pickaxe blow unearthed some roots on which I could see with the naked eye some yellowish spots. A magnifying glass revealed them to be clumps of insects… from this moment, a fact of capital importance was established. It was that an almost invisible insect, shying away underground and multiplying there by myriads of individuals, could bring about the exhaustion of even the strongest vine. (Campbell 50)

Despite this discovery, arguments continued to storm over the true cause of the devastation. ‘The greatly respected Henri Marés … declared it was ‘the severe cold that had continued unbroken last winter that is responsible for the deplorable condition of the vines’ (Campbell 51). The following year Planchon, the entomologist Louis Vialla and Jules Lichtenstein were dispatched by the Agricultural Society of France to continue investigation of the aphid; that summer they received correspondence from the State Entomologist of Missouri, Charles Riley. He wrote that the aphids found by Planchon were in fact the same ones that had been studied in the United States, but that they had not had such a disastrous effect on the vines there (Campbell 68). The scientists had found the cause of the devastation and theorized that it came from America, but no cure was yet in sight. The French Commission on the Phylloxera accepted Planchon’s theories and offered a reward of 20,000 francs to whoever could find a cure for the attacks of the aphid (Campbell 80).

(iii) The Fight Back

A French botanist named Léo Laliman who had both American and European vines in his garden reported to the Agricultural Society of France that the American vines had withstood the phylloxera invasion while the European vines had perished (Campbell 71). He proposed a process called ‘grafting’ vineyards ought to fuse the vines of the European vitis vinifera with the roots of the phylloxera-resistant, vitis varieties from America. This process did not combine the genetics of the two plants but rather formed a compound plant; European vines on American roots. Riley, the State Entomologist of Missouri, confirmed that the phylloxera were not fatal to American vines.

We thus see that no vine, whether native or foreign, is exempt from the attacks of the root-louse. On our native vines however when conditions are normal, the disease seems to remain in a mild state and it is only with foreign kinds and with a few of the natives … that it takes on the more acute form. (Campbell 86)

In her account of the phylloxera infestation Christy Campbell remarks that ‘leaf-galling is not fatal to the vine; nor, on American species, are the root predations. Over millennia of evolution wild vines developed ways to keep the attacker at bay … European vine-roots had and have no such defences’ (Campbell 77).

American resistance had been established but few took note of Laliman’s grafting proposal; grafting was not immediately used as many believed that it would reduce the quality of the grapes produced. Many potential remedies were tested to no avail; Riley remarked that ‘all insecticides are useless’ (Campbell 124). It was not until 1876 that Jean-Henri Fabre reported on his vineyards of ‘grafted Aramons on American varieties’; he said that ‘[the grafted vines] produced no alteration in the quality of taste of the wine nor had any influence on the [resistant] constitution of the roots’ (Campbell 154).That same year Planchon advocated the same thing. ‘While the power of the rootstock directly influences the development of the transplant, the rootstock does not transmit the particular taste which it would have in its own grapes’ (Campbell 160).

Despite rare successes from experimental vineyards grafted onto American rootstock, many still believed that insecticides would be the cure. As such, the French government briefly implemented a ban on the importation of American vines that would prove only to delay the eventual remedy. Lichtenstein, one of the members of the phylloxera investigation, published statements urging the expanded use of grafts. He wrote that ‘the wines of France will live again, reborn on the resistant rootstocks of America’ (Campbell 195).

Campbell describes how ‘slowly, slowly, reconstitution [grafting] took place. When the Beaujolais was officially declared phylloxerated in 1880, the import of alien vines became legal’. According to the French Ministry of Agriculture, about a third of France’s vineyards had been transplanted onto grafted or hybridized vines (Campbell 235).

After twenty years of anguish and effort the vineyards of [southern France] had been put together again. The costs had been great, debts were pressing, but by the mid-1890s the reconstituted vineyards were producing a flood of wine for which there seemed to be no end of thirst. (Campbell 247)

Even into the 1920s there were still un-grafted vineyards surviving on expensive chemical defenses. Today still there are vineyards in Australia, South America, the Middle East and scattered islands that survive on ungrafted vines because of soil conditions or strict controls preventing the movement of phylloxera. But, as noted before, it is estimated that 85% of the world’s vineyards are planted on grafted rootstocks (Oxford Companion to Wine).

(iv) The Battle in Italy

Although the effects of the phylloxera crisis were felt the most in France, it affected much of Western Europe. Professor Battista Grassi estimated that only about 10% of the country’s vines were infected by 1912; ‘the reason for its slow spread was the comparatively isolated nature of Italian vineyards and the habit of growing many vines through trees’ (Ordish 172). The first report of phylloxera in Italy was near Lake Como, but the regions struck hardest were Sicily and Calabria. In a New York Times article published November 8th, 1895 the Italian Consul estimated that lost wages in Sicily in the early 1890s totaled over thirty million dollars (‘Phylloxera Ravages Italy’). Many vineyard owners actually saw the infestation in France as an economic opportunity to export their own wines. In fact, in 1909 five million hectoliters of Italian wine exports to France made up about 10% of the wine consumed by the French (Campbell 249).

As the infestation struck Italy later on and much more slowly, its eradication was much more easily addressed in Italy than in France. Italy, along with many other European countries, enacted a temporary ban on plants that might carry the phylloxera into their vineyards. Vineyards found infected early on were burned at the expense of the state in order to slow the spread (Ordish 173). Although the burning of infected vineyards benefited the Italian wine industry as a whole, there were negative reactions from the owners and workers; in August of 1893 the New York Times reported that ‘the Minister of Agriculture … recently ordered the destruction of vineyards covering a large area in the Province of Novara. The peasants, losing employment through these steps, began to riot. Many were injured in conflicts with the police, and a large number were arrested’ (‘Italian Peasants Rioting’). Once grafting was accepted as a solution the ban on imported vines was lifted in order to supply Italian vineyards with resistant rootstocks subsidized by the government. In fact, another New York Times article published February 2, 1892 indicates that ‘the Italian Minister of Agriculture has for a number of years distributed large quantities of American grape vines among the farmers’ and that ‘from the island of Sicily alone the Minister has received demands for twenty six million rootstocks’ (‘American Vines in Italy’). The government supplied American cuttings and seeds, along with subsidies to farmers planting New World vines (Ordish 173). The Turin Phylloxera Council published their notes from an 1880 meeting, remarking that ‘we, knowing the danger, shall be able in great part to avoid it … Italy having to fight against Phylloxera finds herself in a more favourable position, being abundantly supplied with American vines, which are known to resist the disease’ (Jemina 3). As a result of the later introduction, slower spread and governmental subsidies, Italy’s vineyards were damaged far less than those of France.

‘AMERICAN VINES IN ITALY’ Editorial. New York Times 2 Feb. 1892. The New York Times. Web. 06 Dec. 2010. <http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=FB0D15FC355D15738DDDAB0894DA405B8285F0D3>.

Campbell, Christy. Phylloxera: How Wine Was Saved for the World. London: HarperCollins, 2004. Print.

‘Italian Peasants Rioting’ Editorial. New York Times 4 Aug. 1893. The New York Times. Web. 06 Dec. 2010. <http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=F50D13F93F5A1A738DDDAD0894D0405B8385F0D3>.

Italy. The Turin Phylloxera Council. The Turin Phylloxera Council: Ideas as to the Phylloxera and Rules for Watching the Vineyards. By Jemina. Turin, 1887. John Rylands University Library. Web. 7 Dec. 2010. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/60231304>.

Ordish, George. The Great Wine Blight. London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1987. Print.

‘PHYLLOXERA RAVAGES ITALY’ Editorial. New York Times 08 Nov. 1895. The New York Times. Web. 06 Dec. 2010. <http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=FB0A15FE355911738DDDA10894D9415B8585F0D3>.

Robinson, Jancis. The Oxford Companion to Wine. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999.